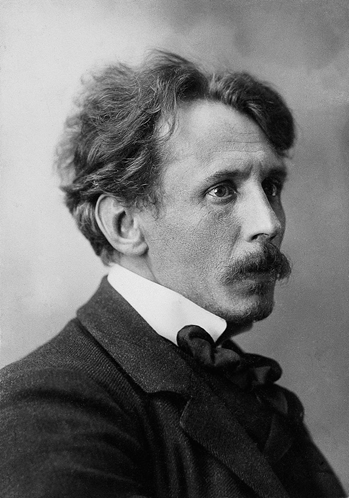

Throughout history, many renowned composers have dedicated significant time to other occupations; Borodin discovered the aldol reaction in his day job as a chemist, Charles Ives was a successful insurance agent, and Paderewski doubled as the prime minister of Poland. Yet few combined their musical and non-musical pursuits as today’s subject, the Lithuanian composer, painter, and writer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis.

Although now known as an advocate of Lithuanian nationalism, Čiurlionis began his life in rather different circumstances. He was born in Senoji Varėna, a town now in southeastern Lithuania but then part of the Russian Empire; as was customary for educated Lithuanians at the time, his family spoke only Polish. At the age of three, his family moved to the nearby town of Druskininkai, where his father had taken up a position as the town’s organist. By that time, Čiurlionis’s musical talent was already being recognized – at the age of three, he began playing music by ear, and he could sight-read easily by the time he turned seven. In 1889, three years after completing primary school, he enrolled in a music school run by a Polish prince in the city of Plungė, learning to play several instruments and graduating in 1893.

Supported by the same Polish prince, Čiurlionis spent the years 1894 to 1899 at the Warsaw Conservatory; it was here that his late Romantic style first began to crystallize, writing a number of works for solo piano, string quartet, and choir, in addition to a now lost sonata for violin and piano. In 1896, with the guidance of the prominent Polish composer Zygmunt Noszkowski, he completed his first major work, the cantata for mixed choir and orchestra De profundis. A richly orchestrated and powerful composition, unquestionably Romantic in quality, De profundis has much in common with Čiurlionis’s more mature works.

Čiurlionis continued his education at the Leipzig Conservatory from 1901 to 1902. The richer musical environment in Leipzig, more attuned to contemporary trends in music, brought further advancements in his compositional career; studies in counterpoint and composition with noted figures like Solomon Jadassohn and Carl Reinecke also played their part. During his time in Leipzig, he composed preludes and fugues for piano, fugues for organ, a string quartet, an overture for full orchestra, and his first (unfortunately unfinished) symphony.

There is no better illustration of the evolution of his musical language in this period than this compilation of piano preludes and a fugue for organ; even through the durations of these short pieces, the tendencies of the music toward less functional and more chromatic harmony are audible.

At the conclusion of his studies in Leipzig, Čiurlionis began exploring other mediums of artistic impression; he took up painting for the first time, and from 1904 to 1906 he studied drawing at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts with the Polish symbolist painter Kazimierz Stabrowski. I don’t wish to spend too much time on his paintings and sketches, as I have no qualifications whatsoever to do so, but his artistic career was equally as successful as his musical one; in six years, he turned out a staggering three hundred(!) pieces of artwork and remains one of the most beloved painters of his time from Eastern Europe. His synthesthesia greatly connected his art and music, and many of his paintings are titled after musical forms like sonatas or fugues. During this time, he also began identifying as Lithuanian when laws passed following the 1905 Russian Revolution removed restrictions on minorities.

Musically, Čiurlionis’s style underwent a significant shift in this period; while many of his works retained a late Romantic idiom, he began experimenting with pitch sets, foreshadowing the atonal music composed by Hauer and Schoenberg a decade and a half later. Some of these ideas, and the overall movement of his music away from standard Western tonal harmony, can be heard in his piano works from the mid-to-late 1900s, including the 1904 “Sefaa Esec” variations, the Four Preludes of 1906, and his 1908 work “The Sea.”

In his orchestral works from this period, Čiurlionis was slightly more conservative in his choices of harmony, but he nevertheless created dazzling universes of sound and color. His masterpiece, Jūra or “The Sea” (not to be confused with the aforementioned piano composition), is by far his most played work – by turns grandiose, expansive, and delicately beautiful.

In 1907, Čiurlionis befriended the art critic Sofija Kymantaitė, who taught him Lithuanian and whom he married two years later; near the end of 1909, he exhibited some of his paintings in St. Petersburg. However, just as he seemed to have the world at his feet, tragedy befell him. When his wife visited him on New Year’s Eve, she found him in deep depression. In 1910, Čiurlionis was brought to a sanatorium near Warsaw, and the following year he passed away of pneumonia at the age of 35.

In 1907, Čiurlionis befriended the art critic Sofija Kymantaitė, who taught him Lithuanian and whom he married two years later; near the end of 1909, he exhibited some of his paintings in St. Petersburg. However, just as he seemed to have the world at his feet, tragedy befell him. When his wife visited him on New Year’s Eve, she found him in deep depression, one from which he never recovered. In 1910, Čiurlionis was brought to a sanatorium near Warsaw, and the following year he passed away of pneumonia at the age of 35. He never saw his daughter Danutė, who at the time was just a year old.

Although his career was tragically cut short in his prime, Čiurlionis was a prolific composer and left more than four hundred works, not counting those that are lost or of which only fragments can be found. We will never know what more might have come from this creative genius – sketches of several orchestral works and even a partially complete opera were found after his death. However, his surviving compositions, especially his later works, display singular harmonic ideas and striking striking originality, not dissimilar in that respect from his contemporary Alexander Scriabin. Who knows – had he lived even as long as Scriabin, perhaps his music would have far greater appreciation today…

I’ll leave you with that thought, and with two more wonderful collections of piano music by Čiurlionis: his “Three Pieces” of 1905 and two enchanting nocturnes!

All the information in this post was derived from Wikipedia and from Ciurlionis’s “official website” at http://ciurlionis.eu/en/music/.

One thought on “The music of Mikalojus Čiurlionis, the multi-talented artist who embodied the Lithuanian fin de siècle”